Beginners may find it useful to make a small reference collection of common species as they get to grips with them, but once that stage is past collections should only be made when needed for scientific purposes. This may be for further investigation, such as microscope work or chemical tests that can’t be carried out in the field, or to send a specimen on to a referee for confirmation.

Never remove all material of a species on a particular substratum. By leaving plenty the species can survive. Specimens that are distorted or atypical will be almost impossible to identify, so ensure that those collected are in good condition.

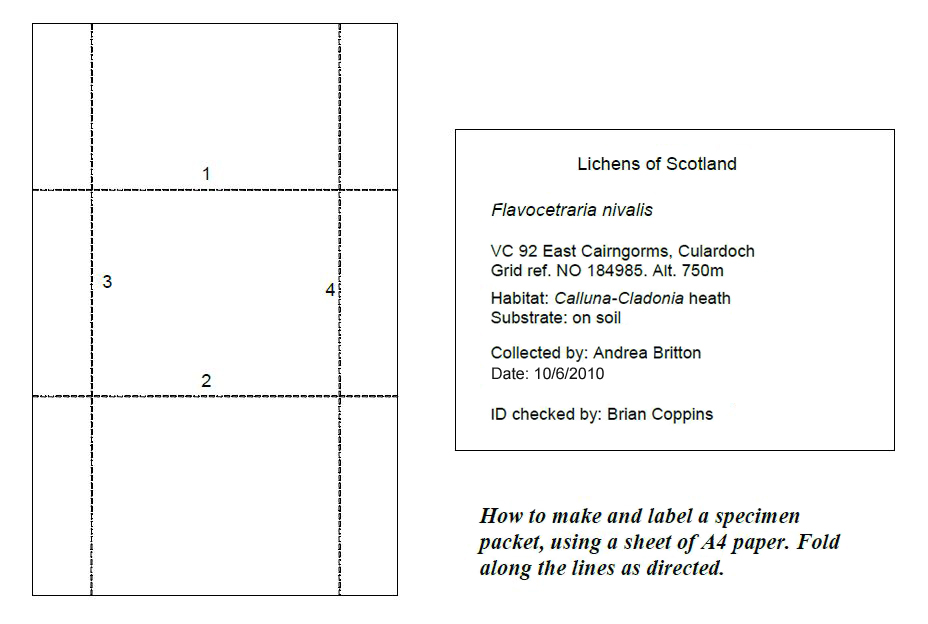

If you do take a sample, either as a reference specimen or a voucher, place each in a separate paper packet (see below). If collecting in wet conditions you will find the bags provided for your convenience when travelling by air or sea to be ideal (!) as they can be left open to allow the specimens to dry naturally. Never use polythene or plastic bags as moist specimens will deteriorate quickly. As an alternative to paper packets, small cardboard containers, tins or plastic compartmentalized boxes (as used for DIY or fishing tackle) are useful for delicate species such as pin-head lichens provided they are dry.

On the packet, or on a slip of paper in the container, record the site name, grid reference (the GPS reading is ideal), date, results of initial spot chemical tests, and initial identification if there is one. For species on bark, note the tree species; on stone note the rock type; on earth or moss, note that and whether the location is sheltered, shaded or humid.

When taking a sample, select a representative part of a thallus which has:

- a good edge (foliose and crustose species);

- a holdfast or basal parts and branch ends in fruticose species such as Bryoria and Usnea;

- examples of mature spore-producing bodies (ascomata);

- asexual propagules such as soredia or isidia;

- a sufficient quantity of material for chemical tests

Leave each packet or other container open to dry; damp lichens go mouldy and are of no use. Specimens should not be dried on hot radiators or in ovens as this may make them unsuitable for molecular studies by specialists.

Once dry, seal the packets in a plastic bag and place in a freezer for two days to kill off invertebrates, such as mites, which are likely to make a meal of your samples. A domestic freezer is adequate for the purpose. Freezing is also recommended if it is likely that molecular work may be undertaken – not necessarily by yourself, but perhaps by a referee to whom it is referred. Make sure that the packets don’t re-acquire moisture by condensation when you take them out of the freezer.

Collecting in the UK

The landowner’s permission (or that of the land manager or tenant if they speak on the landowner’s behalf) should be obtained before collecting, and if the site is a SSSI the permission or consent of the national agency will also be required. In the UK these are Natural England, Natural Resources Wales, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency. It is not always possible to find out who owns land such as roadsides, village greens or commons. It should be noted that having permission to visit, or being on Access Land (CROW Act 2000), does not necessarily imply that you also have permission to collect.

A few species are specially protected under law (e.g. Schedule 8 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981) and licences to collect these must obtained in advance from the appropriate national agency.

Many other species should not be collected without very good reason, and this includes those that are listed as priority taxa for biodiversity in England, Wales (Schedules 41 and 42 of the NERC Act 2006), or Scotland (The Scottish Biodiversity List), are Nationally Rare, or of conservation status Extinct, Critically Endangered or Endangered. The up to date status of every lichen and lichenicolous fungus species can be found in the Taxon Dictionary on this website.

Voucher specimens should be collected for new vice county or national records, but only if this can be done without risking the loss of the population. Your collection may become important evidence for future research and if well preserved could eventually become a valuable addition to a national collection.

Collecting abroad

Most countries have regulations which cover the collection and export of lichens. Overviews with links to original information sources can be found on the JNCC website and for some Central European countries on the webpage of BLAM, the Bryological and Licenological Associationg for Eastern Europe (in German), but in some other parts of the world relevant and up to date information can be difficult to find and is often not fully accessible in English.

By default you can expect that the best way to avoid unpleasant surprises (from the loss of your collection to fines or even jail terms) is to contact local authorities or lichenologists affiliated to national herbaria (seethe website of the New York Botanic Garden for contact addresses) well in advance and ask for advice on current procedures. Best practice is usually a formal collaboration with national herbaria or universities in the visited country.

Depending on the country you are visiting you can expect that up to a year of preparation is a realistic timeframe. Leaving one set of specimens in the country of origin today is usually mandatory under Access and Benefit Sharing regulations, but often a duplicate set can be exported via collaborating institutions.

Donating your collection to a herbarium

Many countries have now signed up to the Nagoya Protocol, and as a result private collections can only be accepted for permanent preservation by national institutions if there is evidence that all specimens were collected legally. Keeping records of permits and consents is therefore as important as the vouchers themselves.