Page in draft

Introduction

Heathlands and moorlands can support rich and varied lichen assemblages, some very visually attractive. This diversity, however, is highly dependant on combinations of grazing, burning and disturbance at differing intensities interacting with the natural characteristics of the soils. In many areas, particularly in the lowlands, however, these lichen assemblages are declining and under threat.

Pycnothelia papillaria in lowland heathland, New Forest & Cladonia zopfii, in moorland, Alladale. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Ecology

Lichens are photosynthetic organisms, so require light to survive. Being small and slow growing this means that they have limited abilities to compete with vascular plants and, for the smaller lichens, even the larger bryophytes. Thus species rich lichens assemblages in moorland and heathland require pressures that reduce plant completion to allow them to flourish. The most basic of these is fertility; low fertile soils in which grass does not readily from dense swards are a basic requirement. Even here further pressures will be needed to open up stands of dwarf shrubs and maintain or restore openness.

Such disturbances can operate periodically or be constant. The main factors which can promote increased lichen diversity include climate, especially frequent exposure to strong winds, grazing, fire and physical erosion, the latter including both natural and man made disturbance. The impact of these is described below.

Disturbance Regimes

Climate

Exposure to strong regular winds is an effective natural way that competition from vascular plants is reduced. This result is wind clipped short heather, and at the most extreme also eroded patches of bare ground. These wind clipped lichen rich heaths can occur both along the coast and and at high altitudes in mountains, especially the Scottish Highlands. At the most extreme these need little other management and are self maintaining, this is especially so in the montane examples. Coastal examples are more likely to be in habitat complexes, where extensive grazing is required to maintain habitat quality. Although such short swards will not normally burn and should not be included within controlled burning cycles, they can be vulnerable to damage from hot out of season wild fires starting in associated taller swards, with fire prone coastal Gorse stands a particular threat. For this reason controlled fire cycles in nearby taller vegetation may be essential to reduce the risk of damaging wild fires impacting these fire refuges.

Wind clipped montane heath, Glen Feshie, close up with Cladonia rangiferina & Cladonia arbuscula. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Summer drought is a significant factor in lowland heaths and parched acid grassland in areas with significant potential water deficits. In heaths, these drought off patches Heather Calluna vulgaris seedlings in regenerating pioneer stands after controlled cool fires. This leads to frequent open bare patches developing in building stages heaths where dense lichen squamules swards establish and prohibit further Heather establishment. These gaps may also be caused by, or extended by, infections by the parasitic plant Dodder Cuscuta epithymum, but drought is the main factor. They can persist as open lichen rich patches right into the mature stage. This contrasts with many upland moorlands with moist summers where few if any gaps develop in the Heather germination in the pioneer stands resulting in dense solid canopies in the maturer stages with little surviving lichen cover. Wherever Cladonia swards do establish in young heather, they can then exclude further heather germination, either by physically or by chemically discouraging germinantion (Hobbs, 1985). In parched acid grassland, the annual dying back of the grass in June, combined with close grazing, also gives lichens an opportunity to survive that is lacking in moist acid grasslands that remain green throughout out summer.

The areas impact by significant summer water deficits are wide spread in lowland England and are reflected in the distribution of parched acid grassland (NVC community U1). They are more limited in Scotland and confined to the east coast but include the lichen rich dunes of north east Scotland. In the uplands they are very limited but parched acid grassland is widespread in the hills of the eastern Marches and up to 300m in south west England.

Grazing

Although lichens are damaged by intensive and closely confined grazing, extensive grazing is a very important factor in promoting lichen richness in many heaths. In many lowland heaths abandonment of grazing has lead to greatly impoverished heaths for lichens. Varying intensities of grazing have different impacts and variations in grazing pressure across sites can promote different assemblages. Very light gazing has limited impact, but moderately levels of grazing that differentially graze down grasses and maintain open heather canopies can increase and prolong lichen diversity on lower productivity soils. Typically such moderate grazing does not prevent the eventual development of tall shaded lichen poor stands of mature or senescent heaths so needs to be combined with periodic controlled burning to rejuvenate the more open and lichen rich younger stages of the heaths.

Moderately pony & cattle grazed lichen rich wet heath and humid heath in the earlier stages of burning rotations with Moorgrass Molinia grazed down, New Forest. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

More intense grazing on more productive heathland and moorland soils can convert, often not very lichen rich heaths, to lichen poor grasslands. In contrast on the most impoverished soils hard grazing can produced very lichen rich short swards. These can still have heather and resemble wind clipped heaths, as in parts of the New Forest, where low productivity soils abut against fertile grasslands. In other very dry soils, as in the Breckland, lichen dominated grasslands are produced. Such short lichen rich swards have different assemblages to the moderately grazed and occasionally burned heaths, and can act as refuges for fire sensitive species as they are difficult to burn. The impact of the loss of rabbit grazing in the 1950s from downland and the Breckland heaths is well known, but the loss of rabbits was also significant in otherwise ungrazed lowland heaths. They probably widely maintained short patches of lichen rich heath but this habitat has been forgotten in many areas. The loss of Hairy Greenweed Genista pilosa from Ashdown Forest can be attibuted to the loss of short grazed prostate heaths which grew up after the loss of rabbits (Rich et al, 1994). The Genista was lost by 1977 to vegetation over growth and hot wildfires. The loss of both Cladonia arbuscula and Cladonia uncialis subsp. biuncialis from Ashdown Forest in the same time frame was likely from the same cause. To the west on the Lizard heaths, rabbits were also important in creating fire refuges in short grazed heath (rock heath) around serpentine outcrops supporting rare fire sensitive rock lichens (Coombe & Forest, 1956).

Hard grazed heaths with high lichen cover, pony & cattle grazed (New Forest) and rabbit grazed (Headon Warren, Isle of Wight). (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Effective grazing needs to be extensive to promote lichen diversity, but also needs to have significant impacts on the vegetation so should not be too light. All grazing animals can have positive impacts if managed carefully. Cattle and Ponies are particularly useful in selectively grazing down coarse grasses and leaving heather but sheep and deer can also promote lichen diversity if not in too high numbers. Rabbits are especially good at promoting impressive bushy growths of reindeer moss but without some additional ground disturbance, diversity of smaller lichens can be low in rabbit warrens.

Fire

Fire is an integral part of heathland and moorland ecology, the dominant vascular plants are burning tolerant, adapted to survive burning, and some, such as Gorse, are strongly fire promoting and are actively evolved to burn to their ecological advantage. As such, heaths are likely burn, whatever the managers intention, and policies of fire suppression have the potential to end in hot uncontrolled wildfires. As such burning vegetation in a controlled manner for predictable results has long been a rational action in the management of heath vegetation, especially as the early stages of recovery from controlled burns produces good grazing for stock and game.

Controlled heather burns in the New Forest, showing removal of loose litter and leaving bare hard humus where well burned but also short grazed areas skipped by the fire producing small fire refuges. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Burning of heath vegetation tends to have a bad reputation in nature conservation, but these takes are often based on the results of hot wildfires, not cool controlled fires. These have very different impacts, with hot wild fire removing the humus layer and with it plant and lichen prologues. This results in colonisation being by outside dispersal, especially for lichens. Thus lichen diversity is initially depressed by hot wildfire, but colonisation can still occur after about a decade. In the 1990s in the unmanaged Dorset heaths the main areas of lichen rich heath were those burned in the drought of 1976; unburned and unmanaged heaths by then were very lichen poor. With controlled cool spring burning carried out when the humus is still damp, the top layer of loose litter is removed but the hard black humus below survives along with plant and lichen prologues (the nature of the lichen prologues is unknown; a research topic!). As such regeneration of new lichen thalli starts the year after the burn and, especially if grazing keeps the heather canopy open, the heaths can remain lichen rich for up to 20 years after the burn (Davies, 2001, Davies & Legg, 2008, Harris et al, 2011, Lee et al, 2013 & Sanderson, 2017). Eventually even with grazing the maturing heather will shade the ground and shade out the lichens completely. As stands senesce they do open up but the litter choked openings are not congenial habitats for specialist heathland lichens, with only a fewer generalist species appearing.

Cladonia incrassata directly surviving a cool burn on a path bank (the pale patch) and squamules of Cladonia strepsilis & Cladonia subcervicornis regenerating from hard humus after a burn, New Forest. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Pippingford Park, Ashdown Forest, a pillow mound in damp heath burned by a cool accidental fire in March 2022 in September 2023, showing regrowing Cladonia peziziformis to right, already supporting fertile podetia after 18 months, also with Bell Heather Erica cinerea seedlings. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Smaller lichens flourishing in post burn regrowth: Cladonia coccifera s. str. in grouse moor, North York Moors & Pycnothelia papillaria in lowland heath, New Forest. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

The sensitivity of heath lichens to burning is very variable and can differ in different climates and soils within species. Some are extraordinarily fire tolerant, with the fungus, but not the algae, of Cladonia strepsilis, remarkably sometimes surviving as live bleached thalli that then sprout new green growth. Others are very intolerant of fire and require fire refuges to survive. Even these can be fire dependant, as the refuges can depend on controlled burning and grazing in the wider landscape reducing the risk of wildfires that would otherwise consume the refuges. Examples include the moderately fire tolerant Cladonia uncialis, which in the New Forest locally regenerates in small short patches of heath which cool burns, but not hot fires, skip over. It can, however, be very more abundant in unburnable short grazed heaths. In contrast in the same area, Cladonia arbuscula does not survive in small open refuges in controlled burns on dry heaths, but does so in wet heaths, where the soil is damper. Again it is also abundant in unburnable short grazed heaths. Many smaller Cladonia species are highly fire dependant as they can not compete with even large Cladonia species let alone vascular plants and flourish in the early stages of regrowth from a cool fire, to latter be displaced by the larger bulky reindeermoss, mainly Cladonia portentosa.

Cladonia uncialis in a small fire refuge in maturing heath. Cladonia arbuscula in unburnable short grazed heath, New Forest. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Rock lichens are different from terricolous lichen assemblages and are invariable negatively impacted by fire and take along time to recover. In upland moorlands small rocks in heaths are unlikely to be very diverse as they will be likely to be impacted repeatedly by either controlled or wild fire before recovering full diversity. Rich rich rocks in these habitats are confined to fire refuges such as rocks in acid grassland or short grazed heaths or large outcrops. It is important in controlled fire programmes to ensure that these rock refuges are not burned.

Isle of Lewis, heather burning spreading into an area with large rocks; not ideal. Alladale, large lichen rich rocks in an area grazed short by deer; a fire refuge.(Click photos to enlarge, © Cris Cant (L) & Neil A Sanderson (R)).

Kynance valley, Lizard Heaths, lefthand photograph, an overgrown rock heath with Cladonia mediterranea and Heterodermia leucomelos. With the high heather cover on the rock and the adjacent tall Gorse this now is very vulnerable to hot wild fires, October 2023. Right, December 2023, the same rock after cutting to open up to grazing and to reduce fire risk (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Kynance valley, Lizard Heaths, although the rocks support fire sensitive lichens, recent work has discovered the remains of a fire dependant lichen assemblage, which has been seriously reduced by vegetation overgrowth. The pictures show a single thallus of the very rare grazing and fire dependant Cladonia peziziformis, new to the Lizard heaths, surviving by a rare open area by a rock slab (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

lefthand photograph, the better grazed rock heath here is acting as a fire refuge; the green area to the right is the site of a recent cool fire that stopped short of the rocks and the Cladonia mediterranea colony (by red phone). Righthand photograph, an overgrown rock heath with Cladonia mediterranea and Heterodermia leucomelos. With the high heather cover on the rock and the adjacent tall Gorse this now is very vulnerable to hot wild fires. (Click to photos to enlarge).

Mowing as an Alternative to Fire

Mowing is sometimes recommended as an alternative to burning to rejuvenate old heather stands, but this treatment does not work very well, for either lichens, or vascular plants that depend on seed germination after fire, especially Erica species. Both require open well lit humus cleared of loose litter and late succession mosses. The these are burned off in controlled burns, but with mowing they remain and the live moss mat smothers the regeneration of both specialist heathland lichens and Erica seedlings. In small relic areas of heath where both grazing and burning are not practical, it may be possible to hand rake off the bryophyte mat and the loose litter to expose the hard humus layer with its propagules. This can be seen to encourage lichen regeneration where mowing cutters have accidentally exposed the hard humus layer, so should work. This should not be confused with conservation “scrapes” that remove the humus layer entirely, along the plant and lichen propagules, and expose the mineral soil, this process is described under soil disturbance.

A recently mown heath stand, showing live moss, loose humus and litter. A very recently burned stand with the moss dead and litter removed. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Soil Disturbance

The open bare ground produced by soil disturbance can provide an important niche for less competitive lichens. To be colonised by lichens some stability and longevity of the habitat after disturbance is required and grazing slowing down vascular plant colonisation can aid the development of lichen diversity. The disturbance can be natural, as in wind eroded areas in wind clipped heaths, stream erosion or, on a large scale, dune systems.

Natural disturbance: an eroding river terrace edge with Trapelia collaris & Ainoa mooreana, Crossone, The Mournes, Co. Down & a colonising blow out at Findhorn dunes with abundant Cladonia zopfii and Cladonia mitis. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Human disturbance can also produce lichen rich open habitats, once the disturbance ceases. On lowland heaths human disturbance is an integral part of the ecological-cultural landscape since their formation. In the New Forest lichen rich habitats can now be found the sides of Bronze Age Barrows, large scale medieval hollow way complexes, 19th century small scale gravel pits, the sites of WWII military activity, modern abandoned gavel pits, tracksides, stock trails and abandoned recreational paths. The modern path erosion is often looked at negatively, but if left to colonise naturally is often richer in species of interest, both lichens and invertebrates, than the adjacent undisturbed heath.

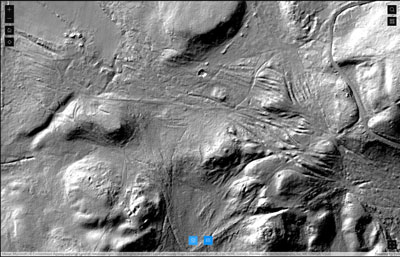

Large scale human disturbance in the New Forest: hollow way complexes at Ogdens (LIDAR from link) in an exceptionally lichen rich heath. (Click photos to enlarge).

Large scale human disturbance in the New Forest: Beaulieu Airfield 1948 and now, an exceptionally lichen rich heath (showing 2012 Wessex Lichen Group meeting route link). (Click photos to enlarge).

Cladonia phyllophora in hollow way at Ogdens & Cladonia firma in heathland bulldozed in WWII, Beaulieu Air Field. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

It is one of the ironies of modern heathland conservation that the bare ground is often created artificially for biodiversity conservation, when this habitat was readily created as a side effect of past exploitation. Small scale conservation scrapes need to be properly evaluated for their effectiveness for lichen conservation. Some results are, as yet, unimpressive, possibly as they have not been combined with effective grazing, and larger scale actions may be more efficient (Sanderson & Cross, 2023). An example is the reactivation of inland sand dunes being carried out in The Netherlands, which has been effective in restoring lichen diversity (Aptroot et al, 2011 & Ketner-Oostra et al, 2010).

Air Pollution

The historic sulphur dioxide impact of pollution on heathland lichens can be difficult to disentangle from confounding factors such as habitat loss and decline, with with all of these tending to occur in areas heavily used by humans, along with changing recorder effort and knowledge. Possibly Cladonia zopfii was been lost in northern England before 1959 due to sulphur dioxide pollution, or possibly it remains undetected; before 2011 it was only known from the south of England from a single 1911 herbarium specimen. It is now known to be very locally frequent in some southern heathlands. Considering only easily identifiable heathland species, declines of Cladonia uncialis subsp. biuncialis and Pycnothelia papillaria are suggestive of losses at least partly to past sulphur dioxide pollution in northern England. In heaths and moors the epicentre of sulphur dioxide pollution, the lowland heaths of the midlands along with the fringes of the southern Pennines and North York Moors, certainly lost much of their lichen and bryophyte diversity. This is reflected in the National Vegetation Classification which recorded the heaths here as supporting a heathland vegetation (H9 Calluna vulgaris – Deschampsia flexuosa heath) with the lowest lichen and bryophyte diversity of any British heaths, with only the pollution tolerant moss Pohlia nutans constant throughout. A sub-community with higher Cladonia diversity (H9a Calluna vulgaris – Deschampsia flexuosa heath, Vaccinium myrtillus – Cladonia spp. sub-community) was recorded in the fringes of the polluted areas. It would be interesting to know if heath and moor lichen diversity in the region has increased recently with the steep decline sulphur dioxide pollution.

The evidence for the modern impact of ammonia based pollution, mainly from intensive agriculture, is better known, mainly from work in the Netherlands in their coversand heaths. Here a significant impact has been shown where high levels of ammonia pollution encourage dense growths of the exotic moss Campylopus introflexus, forming mats several centimetres deep. These exclude both the lichens and native bryophytes. Sparrius (2011) found that “local dominance of Campylopus introflexus was found to occur at N deposition levels of 30-32 kg N ha-1 yr-1 or atmospheric ammonia concentrations of 7 μg NH3 m-3”. This is considerably higher than the critical levels for epiphytic lichens (1 μg NH3 m-3) used in Britain link but also represents the level that eliminates lichen interest. This suggests that the critical level of (3 μg NH3 m-3) used for terricolous vegetation in Britain would be the most appropriate one for heathland lichens. This supported by observations of very healthy central English heathland with rich lichen assemblages surviving in areas with ammonia levels that were having a strong impact on the lichen epiphytes. Similar high cover of Campylopus introflexus can be seen on the sites of hot wildfire on heaths, where the humus has survived but the high temperature has cooked it and thereby increased the available nitrogen.

Reduction in the pollutant is the obvious mitigation for current locally high ammonia pollution. Restoring management in abandoned heaths and increased management intensity, such as ground disturbance, may somewhat reduce losses, but these are likely to be ineffective at high levels of deposition.

Lower levels of pollution potentially have negative impacts less drastic than the total losses described above but are difficult to study. A major long-term resurvey of Scottish moorland plots after 35 years with numerous parameters analysed is particularly interesting (Britton et al, 2016) in illustrating this complexity. It is especially useful in that it covers sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide and ammonia pollution separately, something not all studies do. This found general declines in lichen cover over 35 years, but with this mainly correlated to climatic factors generally, but also with a negative correlation with nitrogen oxide deposition in dry heath. In the data for all groups, however factors other than pollution were more important and interestingly recovery from past sulphur dioxide pollution was more marked in some groups other than lichens than impacts from nitrogen deposition.

Buckherd Bottom, New Forest 2013: contrasting responses to a late 1980s hot summer burn: a dense mat of Campylopus introflexus and no lichens where "cooked" humus survived the fire increasing available nitrogen but a rich Cladonia – Polytrichum community where the fire burned right through the humus exposing impoverished nitrogen poor gravel below. (Click photos to enlarge, © Neil A Sanderson).

Assessment

Heathland and moorland lichen assemblages are not nearly as well recorded as epiphyic assemblages, and the extent of lichen rich stands is not as well known. They are rare in many areas, but alternatively Cladonia enthusiasts have recently stumbled on some exceptrionally rich but compeletely unknown sites, especailly in Scotland. To aid assessment of these habitats Sanderson et al (2018) have produced the Heathland, Moorland and Coastal Heath Index (HMCHI). This built on the work of Sanderson (2017), with the Cetraria, Cladonia and Pycnothelia index (CCPI) developed for southern England heathland augmented to cover all non-montane heaths, including non-montane moorland, coastal heathland, acid dunes and comparable habitats. For hard rock coasts and associated grassland communities, use Maritime Rock and Coastal Slope Index

The index should be applied to a heathland or moorland area of about 100ha. The index score is calculated by adding the number of recorded taxa in each genus listed in the left-hand column of table below to the number of recorded species in the right-hand column. For example, a site supporting 23 Cladonia taxa, two Cetraria taxa, Pycnothelia papillaria and Leptogium palmatum, would score 27.

Sites scoring 20 or more were regarded as being of national importance. This is a high score, as the full extent of the resource was not known, and in many area sites scoring 15 or more will be rare and significant, while a score of 10 or more indicates a site of at leats loc al interest.

| Genera | Species |

| Alectoria | Scytinium palmatum |

| Bryoria | Ochrolechia frigida |

| Cetraria | Peltigera malacea |

| Cladonia | Stereocaulon condensatum |

| Heterodermia | Stereocaulon glareosum |

| Icmadophila | Usnea articulata |

| Pycnothelia | |

| Teloschistes | |

| Thamnolia |

In calculating the index, include species that occur on heather stems, but not those on rocks. In Cladonia count all recognised infraspecific taxa. For the Cladonia chlorophaea s. lat. group, if possible count Cladonia chlorophaea s. str. and Cladonia grayi s. str. individually, but treat the remainder of Cladonia grayi s. lat. as a single aggregate, (best called the Cladonia cryptochlorophaea group).

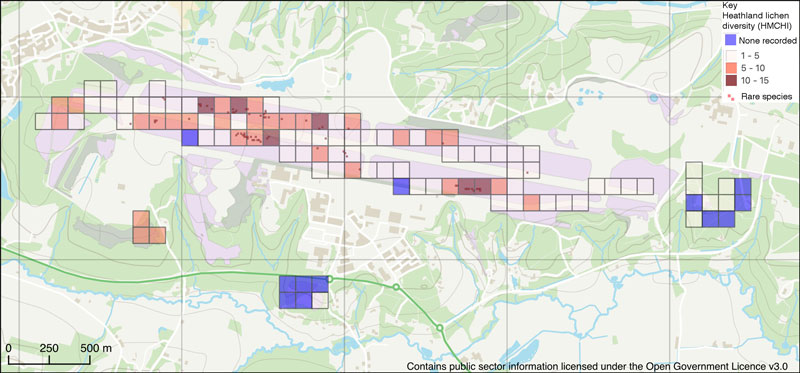

Species lists can be made at a site level but more intensive survey work can sytematically survey heaths on a grid. At a landscpe scale in very extesive heaths or moorlands then a 1km grid can be used, but typically in planning or conservation surveys of indavidual heaths then a 100m grid is best. This is time consuming to collected but will allow mapping of species diversity across heaths and individual species distibutions to be determined.

A map showing the density of Heathland, Moorland and Coastal Heath Index (HMCHI) species at Greenham & Crookham commons Berkshire (Sanderson & Cross, 2013). Shows species rich areas in short grazed patches of heath contrasting with species poor ungrazed heath to the south and west. Created using QGIS & the TomBio plugin (Click for larger version).

Restoration

Heathland and moorland restoration includes returning sustainable management to negelected heaths, the recreation of destroyed habitat and the recovery of over intensively managed habitat.

The former is the most likely to produce high quality lichen habitat most rapidly, as relic populations of specialist lichens can survive and lichen propagules potentially remain in the soils. Recreation of destroyed habitat will be easiest from conifer plantations planted on intact heathland soils. This will produce good lichen habitat rapidly, but observations to date (Sanderson, 2017) suggest that heathland specialist species are rare with mainly more widespread lichens dominating in the first decade or so at least. Restoring from more disturbed soils such as arable, is likely to be a much more long term prospect for lichens, but could produce interesting results of sandy soils eventually.

With overgrazed sites, mainly moorland, the main difficulty will be devising sustainable grazing systems to replace the over intensive subsidy driven grazing of the latter part of the 20th century. In many, miss grazing rather than over grazing, is more the issue; typically with too few course grass graziers such as cattle and ponies and too many sheep. Simply reducing grazing pressures with out addressing grazing imbalances can result in as many problems as it solves, with smaller species such as lichens lost to increased grass growth. Clouston (2021) gives a detailed account of the complexities of restoration in such situations.

In heathlands and moorlands, as in other habitats, over cautious conservation management is a frequent problem, with the resultant taller shadier swards a poor habitat for lichens (Timmermann et al, 2015 & Sanderson & Cross, 2023), Conservationists are failing to conserve by careful management the biodiversity richness that commoners and farmers produced by happenstance in the past.

Grazing:

- Grazing is an essential part of heathland management and should be revived or maintained where possible.

Where there is room, varied grazing pressures should be aimed for. - On larger sites some areas of heavily browsed short Heather should be accepted.

- Grazing animals should include at least some course grass graziers such as cattle and ponies.

- If Rabbit populations revive, their localised hard grazing is to be valued for creating short open lichen rich swards.

Burning and Mowing:

- Most heaths will be grazed at level that allows Heather swards to mature across large areas of the site. To maintain lichen diversity in these, effective cyclic management to rejuvenate the swards is required.

- To be effective treatment to rejuvenate the stands needs to remove the top layer of late succession mosses and loose humus to expose lichen propagules and Calluna and Erica seeds in the compacted humus below.

- Prescribed burning does this effectively and should be deployed wherever possible. Mowing does not and should be used as little as possible.

- Where prescribed burning is not possible raking off patches of the top layer of late succession mosses and loose humus in mown areas could be experimented with.

Disturbance:

- Disturbance exposing raw bare soil that takes many decades to fully revegetate is an important habitat supporting lichen diversity.

- This is most easily developed where the grazing is heavier.

- Smaller conservation scrapes in lightly or ungrazed situations appear ineffectual as lichen conservation measures; they revegetate too fast.

- Large disturbed areas, with a mix of very shallow disturbance exposing hard black humus along with deeper excavations with steep consolidated sides are likely to be more effective.

- A good deal of recreational path erosion, where it creates complex rutted topographies that then force abandonment and shifting paths has proved to be more effective than conservation scrapes at promoting lichen diversity.

- Valuable features need to be protected, but a less precious attitude to heathland erosion would aid lichen conservation.

- In heathland restoration slow colonisation of bare surfaces, as in old gravel pits, that takes decades, is far more likely to promote lichen diversity than more intrusive methods of rapidly creating dense Heather swards.

To quote (Proctor, 2013):

“A heath long-unburnt tends to be a very dull place, and heathland managers who will not use burning for management bear a heavy burden of guilt for declining biodiversity in our heathlands.”

Neil A Sanderson, December 2023

References & Further Reading

Aptroot, A., van Herk, K. & Sparrius, L. (2011) Korstmossen van Duin, Heide en Stuifzand. Bryologische en Lichenologische Werkgroep van de KNNV.

Britton, A.J., Hester, A.J., Hewison, R.L., Potts, J.M., Ross, L.C. (2016) Climate, pollution and grazing drive long-term change in moorland habitats. Applied Vegetation Science. 20:194-203.

Byfield, A. & Pearman, D. (1996) Dorset’s Disappearing Heathland Flora. Changes in the Distribution of Dorset’s Rarer Heathland Species 1931 to 1993. Plantlife & RSPB.

Chatters, C. (2021) Heathland. British Wildlife Collection 9. Bloomsbury Wildlife; London.

Clouston, A. (2021) Stakeholder Narratives of Dartmoor’s Commons: Tradition and the Search for Consensus in a time of Change. PhD Thesis: The Centre for Rural Policy Research University of Exeter.

Coombe & Frost (1956) The heaths of the Cornish Serpentine. Journal of Ecology. 44: 226-256

Davies, G. M. (2001) The Impact of Muirburning on Lichen Diversity. University of Edinburgh:

Davies, G. M. & Legg, C. J. (2008) The effect of traditional management burning on lichen diversity. Applied Vegetation Science 11: 529-538.

Harris, M. P. K., Allen, K. A., McAllister, H. A., Eyre, G., Le Due, M. G. & Marrs, R. H. (2011) Factors affecting moorland plant communities and component species in relation to prescribed burning. Journal of Applied Ecology 48: 1411-1421

Hobbs, R. J. (1985) The persistence of Cladonia patches in closed heathland stands. Lichenologist 17: 103-110.

Ketner-Oostra, R., Sparrius, L. B. & Sykora, K. (2010) Development of lichen-rich communities. In: Inland Drift Sand Landscape (J. Fanta & H. Siepel, eds): 235-254. Zeist, Netherlands; KNNV Publishing.

Lee, H., Alday, J.G., Rose, R.J., O’Reilly, J., Marrs, R.H. (2013). Long-term effects of rotational prescribed-burning and low-intensity sheep-grazing on blanket-bog plant communities. Journal of Applied Ecology 50: 625–635.

Proctor, M. (2013) Vegetation of Britain and Ireland. Collins New Naturalist Library, Book 122. Collins; London.

Rich, T., Donovan, P., Harmes, P., Knapp, A., Marrable, C, McFarlane. M., Muggeridge, N., Nicholson, R., Reader, M. Reader, P., Rich E. and White, P. (1996) Flora of Ashdown Forest. Sussex Botanical Recording Society.

Sanderson, N. A. (2017) The New Forest Heathland Lichen Survey 2011 – 2015. Natural England Joint Publication JP020. Peterborough; Natural England. Link

Sanderson, N. A. Wilkins, T., Bosanquet, S. & Genney, D. (2018) Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs. Part 2: Detailed Guidelines for Habitats and Species Groups. Chapter 13 Lichens and associated microfungi. Joint Nature Conservation Committee 2018: Peterborough. Link

Sanderson, N. A. & Cross, A. M. 2023. Lichen Diversity and Heathland Management in West Berkshire and North West Hampshire. A Botanical Survey & Assessment Report to Natural England

Sparrius, L. B. (2011) Inland dunes in The Netherlands: soil, vegetation, nitrogen deposition and invasive species. Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam.

Timmermann, A., Damgaard, C., Strandberg, M. T. & Svenning, J-C. 2015. Pervasive early 21st-century vegetation changes across Danish semi-natural ecosystems: more losers than winners and a shift towards competitive, tall-growing species. Journal of Applied Ecology 52: 21–30.