Pycnothelia papillaria

Cladonia papillaria f. molariformis

A distinctive ground growing lichen of heath and moorland consisting of a white crust studded with small tooth like podetia.

Basal thallus persistent and crustose, grey-white or cream and consisting of contiguous granules, occasionally sub-squamulose. Podetia short, typically to 0.5cm, rarely up to 2cm, erect, barrel or tooth like, usually simple but can be branched and coralloid if well grown, whitish with brown tips. Pycnidia frequent, visible as up to ten tiny ostioles on the branch tips. Apothecia rare, dark red-brown and on short stalks.

Reactions: thallus C–, K+ yellow, KC–, Pd–, medulla UV± blue-white (atranorin, ± chloratranorin, d-protolichesterinic, lichesterinic and ± squamatic acids).

The tooth like podetia are nearly always present and are highly distinctive.

Found on acid peat, humic layers over leached, very acid soils or shallow humus over rock in heathlands and moorlands. This lichen is found on firm, sometimes compacted, black humus and it is absent from both bare mineral soil or loose fibrous humus. It is light demanding and is strongly dependant on grazing, fire or disturbance to maintain open conditions. It is typical of unshaded open patches in low productivity or short grazed swards, on damp to seasonally wet humus. It avoids permanently wet peat. It is among the most tolerant heathland lichens of trampling and can survive on the edges of paths and in scuffed open acid grassland swards. It is also reasonably fire tolerant and thrives in heathland under controlled burning regimes that expose hard black humus surfaces. It will be lost, however, where hot fires burn away the humus layer to leave only mineral soil.

The requirement for humic rich soils means it does not benefit, at least in the short term, from gross soil disturbance, such as conservation turf stripping in lowland heathlands. This species in particular, and lowland heathland hard humus specialists in general, have been noted as not responding positively to turf stripping or reactivation of inland dunes in the Netherlands. Strong colonisation of features such as WWII gravel pit bases in the New Forest, however, suggests that colonisation will occur if the ground remains open for decades, allowing humus accumulation.

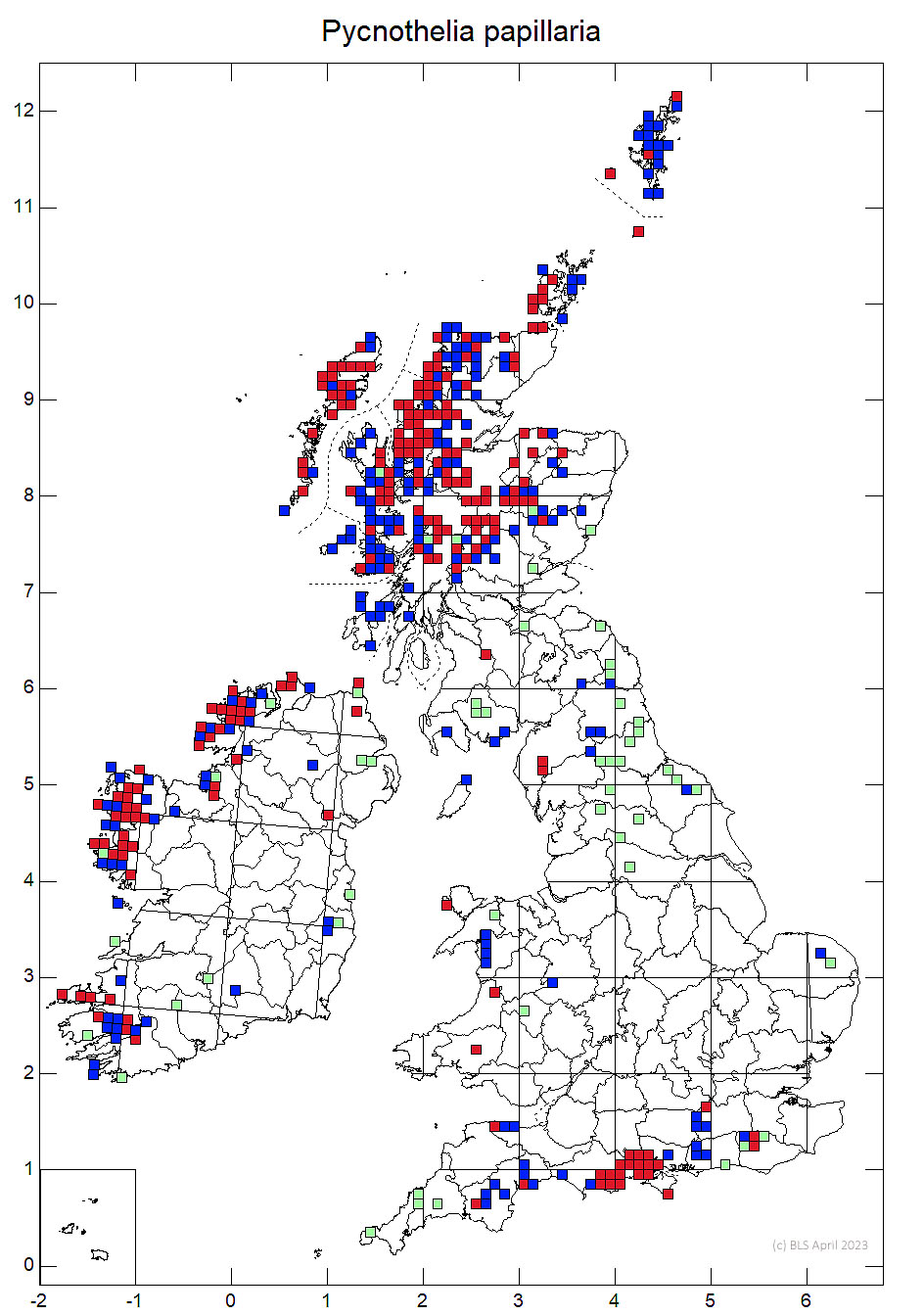

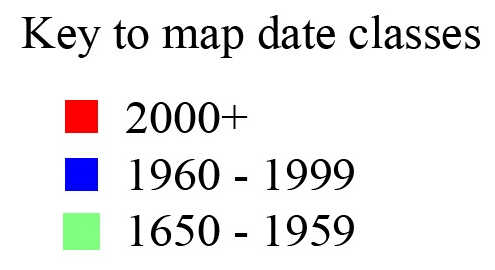

Pycnothelia papillaria has a distinct British distribution, shared by other heathland species such as Cladonia strepsilis and Cladonia zopfii. It is frequent in the Scottish Highlands and locally frequent in southern lowland heathland south of the River Thames but rare in the uplands between. There are a large number of pre-1960 records from the north of England, suggesting a significant decline in this area; most probably due to 19th & 20th C SO2 pollution. The rarity in some upland clean air areas south of the Scottish Highlands, however, must have other causes. It is most likely due to the rarity of very low productivity habitats such as the heavily leached and pre glacial soils of the southern heathlands and shallow rocky blanket bogs of the Highlands. Recently a strong decline has been detected in lowland heaths outside of the New Forest, related to a reduction in grazing and a lack of controlled burning of heaths. It is still abundant in the New Forest, where a recent systematic survey recorded Pycnothelia papillaria from 75 out of 100 1km grid squares sampled.

In Ireland it is widespread in moorland to the west but rare in the east.

This species is highly threatened across the European lowlands from the Netherlands to Latvia and is also suffering a severe decline south of the Scottish Highlands, except in the New Forest. It is assessed as Near Threatened in Wales. In the New Forest it is still widespread and locally abundant with traditional heathland management providing frequent well lit hard humus surfaces. The main positive factors are extensive but locally heavy range grazing, controlled burning and accidental and occasional soil disturbance. Air pollution is also implicated is some losses but it has been equally lost from clean air areas where traditional management has stopped.

Probably much less threatened in the northern uplands but could decline with abandonment of tradition moorland management.

Ahti, T. & Stenros (2013) Pycnothelia. In: Nordic Lichen Flora, Volume 5 Cladoniaceae (ed. T. Ahti, S. Stenros & R. Moberg) 89-90. Uppsala: University of Uppsala.

Ketner-Oostra, R., Sparrius, L. B. & Sykora, K. (2010) Development of lichen-rich communities. In: Inland Drift Sand Landscape (J. Fanta & H. Siepel, eds): 235-254. Zeist, Netherlands; KNNV Publishing.

Lambley, P. & Purvis, O.W. (2009) Pycnothelia Dufour (1821). In: The Lichens of Britain and Ireland (C. W. Smith, A. Aptroot, B. J. Coppins, A. Fletcher, O. L. Gilbert, P.W. James & P. A. Wolseley, eds): 773. London: British Lichen Society.

Haveman, R. & Ronde, I. de (2013) Pycnothelia papillaria (rijstkorrelmos) in het Harskampse Zand. Buxbaumiella 95: 48-53.

Sanderson, N. A. (2016) The New Forest Heathland Lichen Survey 2011 – 2015. A report by Botanical Survey & Assessment to Natural England, Forest Enterprise & The National Trust. Link.

Zarabska, D. & Rosadziński , S (2011) New records of the lichen species Pycnothelia papillaria in Poland in the context of new records. Botanika – Steciana 15: 149-152.

Text by Neil A Sanderson, based on Lambley & Purvis (2009)