What are ‘Indices of Ecological Continuity’?

These are methods for assessing the conservation importance of woodland sites for their lichen interest. To evaluate and compare the lichen interests of deciduous (broad-leaved) woodlands and Native Pinewoods sites in Britain various criteria are applied, particularly Indices of Ecological Continuity.

The Indices are based on lists of Indicator Species, selected to enable woodlands to be graded for their conservation status and the ‘quality’ of their lichen flora. The species are usually epiphytic lichens characteristic and indicative of ancient old growth woodland, drawn up from lists originally made through the pioneering work by Francis Rose in the 1970s. Through later collaborations and input from other lichenologists, particularly Brian Coppins, the Indicator Species lists were refined, tested and collated from many years of extensive fieldwork and data collecting, and were eventually published in 2002 (Coppins & Coppins 2002).

The indices were reviewed in 2018 by Sanderson (in press) as part of drawing up new guidelines for SSSI selection (Sanderson et al 2018). This review recommended minor changes to some indices, particularly removing the awkward to use species pairs, or groups of species, which only counted once, even if more than one species was present. A few of the indices were found to need a little bit more reconstruction, mainly replacing several species with others that were of more utility. The replacement indices are now the accepted versions used in the published Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs for Lichens. Given that all the indices were changed to some degree, they were all given new, and in some cases more informative, names. In addition, a new index, the Pinhead Lichen Index was devised.

The Indices are divided into regional and climatic categories, devised to reflect the variation in lichen communities and species present within the geographical and climatic range in the British Isles. Hence, there is the Lowland Rainforest Index (formerly the Western Scotland Index of Ecological Continuity), applicable to areas experiencing the mild, wet Atlantic climate of the lower ground in coastal Western Scotland.

In Britain, government and non-government conservation agencies require data on the conservation importance of candidate Special Areas of Conservation) SACs, National Nature Reserves (NNRs) and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). Lichen surveys are commissioned and the results written up in a site report, which will include (at least) total number of lichen taxa and the values of appropriate Lichen Indices. This enables sites of international, national, regional and local importance to be recognised, and appropriate action to adequately manage and protect the lichen interest to be taken. Details of individual site reports are added to the Unpublished Grey Literature lists.

The use of the lists of Indicator Species must be seen as a broad brush assessment, and not an infallible guide.

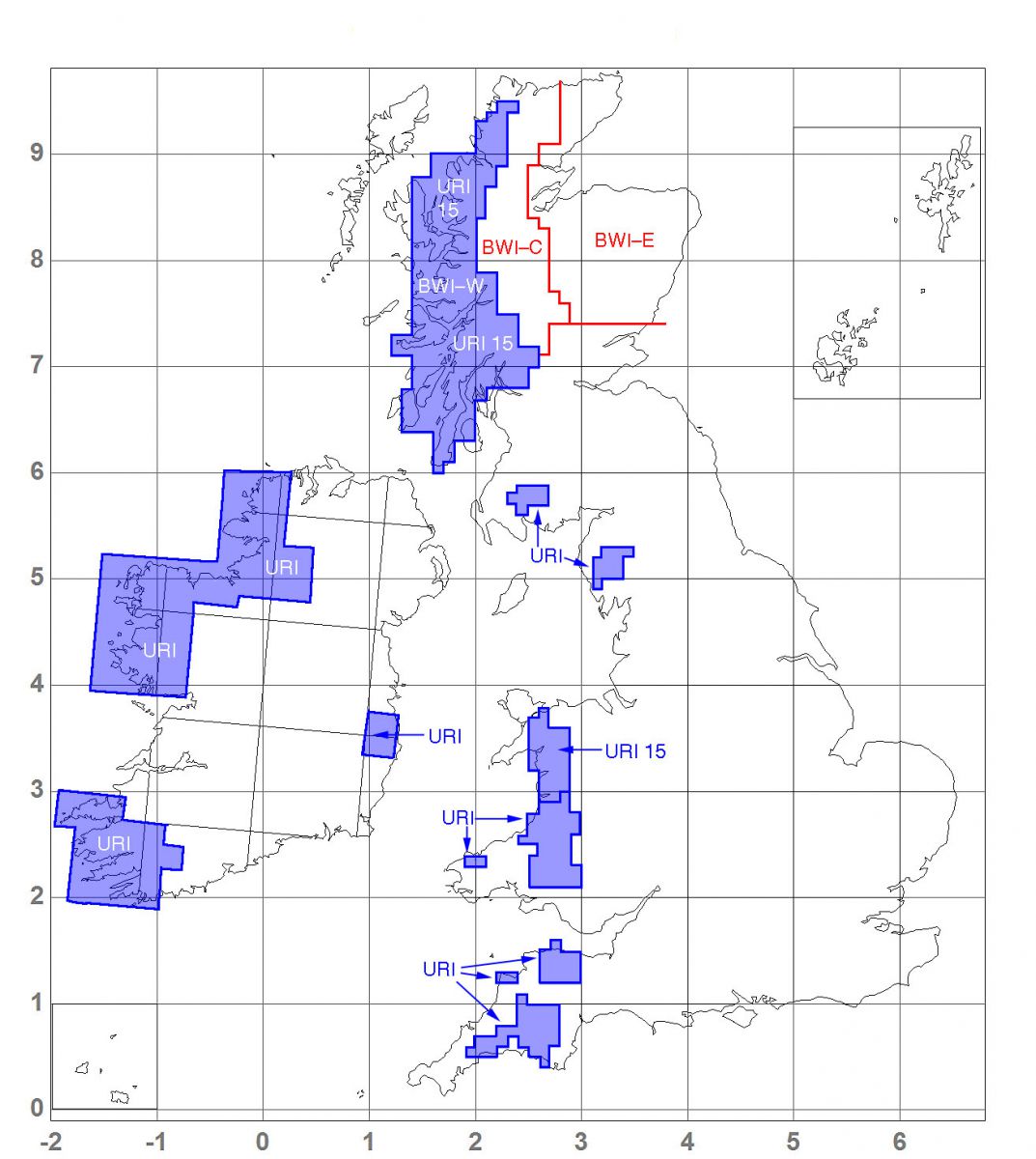

Map showing areas where each lichen index for lowland/temperate woodlands is appropriate.

.jpg)

Map showing areas where each Lichen Index for Ecological Continuity for upland/boreal woodlands is appropriate.

URI* = Upland Rainforest Index (replaces the Eu-Oceanic Calcifuge Index of Ecological Continuity )

BWI = Boreal Woodland Index (E = Eastern pinewood zone, C = Central pinewood zone and W = Western pinewood zone) (replaces the Native Pinewood Index of Ecological Continuity)

A coincidence map showing the cumulative distribution of the lichens used in the Pinhead Lichens Index

.jpg)

The new Pinhead Lichens Index is proving especially useful in pasture woodlands and parklands with large amounts of dead wood in formerly polluted areas, where the pinhead lichens appear to be recovering much faster than other old woodland assemblages

Ancient woodlands: ‘Ancient’ woods are taken to mean sites that have been continuously wooded since 1600 (Peterken 1974, 1996, 2000; Rose 1999). Generally, ancient woods are considered to be of greater conservation importance, as they will tend to support the greatest biodiversity. Using lists of Ancient Woodland Vascular Plants (flowering plants) as an aid to identifying ancient woodland sites and evaluating their nature conservation importance is well established and commonly used (Peterken 1974, 1996, 2000; Rose 1999).

In the 1970s, Francis Rose recognised that lichens could also be used to identify ancient woodlands. Making species lists of lichens from woodland habitats throughout Britain, it soon became clear that although some woods that were known to be ancient from both documentary sources and Ancient Woodland Vascular Plants lists, they did not support the anticipated diversity of epiphytic lichens. Why was there this discrepancy? There were two main reasons: atmospheric pollution, and woodland management.

Atmospheric pollution

In areas recently or historically affected by high levels of acidifying atmospheric pollution or acid rain, there will have been a huge negative knock-on effect on the lichen flora. Many, if not most, lichens on trees in badly affected areas of lowland England, will have suffered lichen impoverishment since the Industrial Revolution. Today, recording lichens from many known ancient parklands in central lowland England, the species lists will not reflect their antiquity. There is a reduced lichen flora, mainly of species able to tolerate enhanced levels of SO2 pollution, and latterly, with reduction in background acidity in the atmosphere and enhanced eutrophication from intensive agriculture, there will be a change, from acid-tolerant species to lichens associated with eutrophic conditions. There are currently, massive invasions of lichens back into these ‘lichen deserts’, but not by the ‘old woodland’ Indicator Species, or species indicative of Ecological Continuity.

One brighter note is that recent surveys of parks and pasture woodlands, which were impacted by pollution in the latter 20th century and were more or less written off as lichen habitats, have proved to have a greater degree of survival of some of the original rare species than was thought. Although much has been lost, some species just survived in protected niches and now have the potential to recover. Examples include Lecanora sublivescens in Windsor Forest; Pyrenula nitida, Pyrenula nitidella, Bellicidia incompta (Bacidia incompta), Scutula circumspecta (Bacidia circumspecta) and Thelopsis rubella at Burnham Beeches and Bellicidia incompta (Bacidia incompta) and Thelopsis corticola (Opegrapha corticola) at Hatfield Forest.

Woodland management

Over the centuries, no woodlands have escaped some degree of modification and management – indeed, woods only survived because they were useful to man and were managed to produce useful commodities, for sheltered grazing or for sport (e.g. deer parks). This does not mean that today’s woods do not occupy ancient woodland sites, and will retain features which mark them out as such. Ancient woodland sites largely retain their associated woodland ground flora, despite intensive management. Coppiced woods for example (where trees were cut back on a regular cycle such as Oak for charcoal and tanning, and Hazel for a whole range of small wood uses) are often known to support species-rich flowering plants. However, with lichens, clear-felling and coppicing has severe implications on the epiphytic lichens of woodlands. If a woodland has been clear-felled at any time during its history, then all the associated lichens would go with the extraction of the felled trees. The flowering plants of a woodland ground flora (where the seed-bank remains in the ground), are able to survive clear felling if the woodland is quickly regenerated or planted with deciduous trees. Lichens, however, are removed with the cut timber, and although lichen propagules blowing around in the atmosphere are able to establish on young trees as the woodland re-grows, these will be widespread and common woodland epiphytes. The critical ‘old woodland’ lichens will be lost, those species dependent on continuity of woodland cover and specialised niches, and some exclusively dependent on the continual presence of old trees (Rose 1976, 1992). In Native Pinewoods, this habitat dependency also extends to the continual presence of dead trees.

Widely recognised terms used to described the structural difference between the lichen-poor heavily managed woods dominated by young trees and the lichen-rich less intensively used woodlands with old and standing dead trees are young growth and old growth stands (Alexander et al, 2002). Features defining old growth wood begin to develop in most British woodland types in stands of 200 or more years of age. The richest lichen sites, however, usually have a much older continuity of old growth features than this. Most British lichen-rich old growth stands have their origins in long grazed pasture woodlands or ancient deer parks; multi-use systems were efficient timber or wood production was not possible and populations of veteran trees could survive within managed landscapes.

The degree of woodland habitat disturbance over time is therefore important for lichen communities. Woodlands – or parklands – that have retained degrees of continuous woodland cover and old growth conditions are likely to support old woodland lichen communities. The common purpose of all the Lichen Indices is that they indicate ecological continuity within a woodland, the theory being that the more critical species (the ones of conservation importance) are poor colonizers and require regular availability of suitable habitat niches within the woodland ecosystem.

References:

Alexander, K.N.A., Smith, M., Stiven, R. & Sanderson, N.A. (2002) English Nature research Reports No 494. Defining ‘Old Growth’ in the UK Context. Peterborough: English Nature.

Coppins, A. & Coppins, B.J. (2002) Indices of Ecological Continuity for woodland epiphytic lichen habitats in the British Isles. British Lichen Society.

Fletcher, A., Coppins, B.J., Hawksworth, D.L., James, P.W. & Rose, F. (1982) Survey and Assessment of Epiphytic Lichen Habitats. A report prepared by the Woodland Working Party of the British Lichen Society, for the Nature Conservancy Council [contract HF3/03/208].

James,P.W., Hawksworth,D.L. & Rose, F. (1977) Lichen communities in the British Isles: a preliminary conspectus. In: Lichen Ecology (ed. M.R.D.Seaward): 295-413. Academic Press, London.

Peterken, G.F. (1974) A method for assessing woodland flora for conservation using Indicator species. Biological Conservation 6: 239-245.

Peterken, G.F. (1996) Natural Woodland, Ecology and Conservation in Northern Temperate Regions. Cambridge, New York & Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Peterken, G.F. (2000) Identifying ancient woodland using vascular plant indicators. British Wildlife 11: 153-158.

Rose, F. (1976) Lichenological indicators of age and environmental continuity in woodlands. In Brown, D.H., Hawksworth, D.L. & Bailey, R.H. (eds), Lichenology: Progress and Problems: 278–307. London etc.: Academic Press.

Rose, F. (1992) Temperate forest management: its effect on bryophyte and lichen floras and habitats. In Bates, J.W. & Farmer, A.M. (eds), Bryophytes and Lichens in a Changing Environment: 211–233. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rose, F. (1999) Indicators of ancient woodland: the use of vascular plants in evaluating ancient woods for nature conservation. British Wildlife 10: 241-251.

Sanderson, N.A. Wilkins, T., Bosanquet, S. & Genney, D. (2018) Guidelines for the Selection of Biological SSSIs. Part 2: Detailed Guidelines for Habitats and Species Groups. Chapter 13 Lichens and associated microfungi. Joint Nature Conservation Committee 2018: Peterborough Link

Sanderson, N.A. (in press) A review of woodland epiphytic lichen habitat quality indices in the UK. A report by Botanical Survey and Assessment to Natural England.